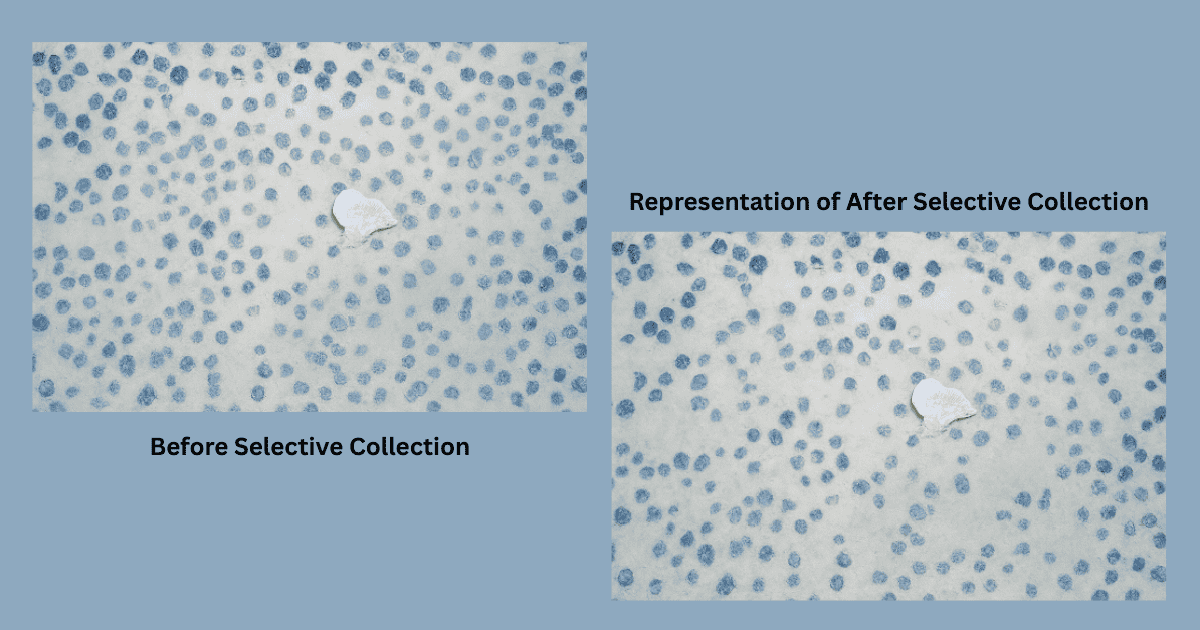

A key feature of the Eureka collection system is the selective collection technology Impossible Metals has incorporated into the vehicles, which allows for the programming of a percentage of nodules to remain undisturbed. In addition to leaving a percentage of nodules undisturbed to serve as habitat for subsea life that lives among them, the technology also identifies megafauna and leaves a wide swath around all detected life.

Life detection demo in the tow-tank. (Video credit: Impossible Metals)

In response to a report delivered by the Deep Sea Mining Campaign, Impossible Metals began to further explore the collection aspect of their Eureka collection system.

Referencing one of the statements found in the report, “It could be concluded that Impossible Metals’ extraction targets are based on financial rather than ecological imperatives, as no scientific basis has been presented for the assertion of sustainable or selective nodule mining. As such these targets are unlikely to maintain ecosystem viability and function. Ecological consequences would only become evident through long term studies, by which time the impacts of commercial mining are likely to be irreversible in human timeframes,” Impossible Metals expanded further on the percentage of nodules being collected.

Impossible Metals based the target of 30% left behind on 30×30, which specifically calls for the effective protection and management of 30% of the world’s terrestrial, inland water, coastal, and marine areas by the year 2030. The company had previously assumed that increasing the percentage of nodules collected would reduce their economics, just as DSMC assumed in their paper. Impossible Metals wanted to explore and understand at what point the Eureka collection system is no longer profitable. By reducing the percentage of nodules collected and re-optimizing their design for this new target, Impossible Metals found that, counterintuitively, profitability is increasing. There are two key economic drivers at play when adjusting the percentage collected for the area travelled over. Travel speed is one, and nodule size is the other. Maintaining the same mass throughput while collecting a lower nodule density requires the vehicle to travel faster. Since the company’s cost of increased travel speed is relatively modest, there is not a meaningful downside to traveling faster and leaving a high percentage of nodules undisturbed. Nodule size is the other factor, and since their cost per pick is relatively consistent, by traveling faster over the seafloor and picking only the highest-value (largest) nodules, Impossible Metals reports that it can leave a high percentage of material behind while increasing their profitability.

The assumptions used in Impossible Metal’s analysis were NORI-D and nodule size distribution, based on the most recent TMC pre-feasibility study.

By running several simulations for both the Eureka III-sized (4MT) and Eureka IV-sized (12MT) vehicles, starting at 2%, then 5%, up to 100% at increments of 5%, the cost per tonne of nodules to port for each increment was calculated.

As expected, as the percentage of nodules collected approaches zero, the cost per tonne of material to port starts to jump up. However, before that, good economics are achieved at surprisingly small percentages. When collecting all sizes of nodules equally at between 10% to 20% of the nodules, the economics reach a peak, and there is no difference in economics in increasing the density of nodule collection. When simulating selection for the most valuable nodules, Impossible Metals found that their peak economics occur when collecting approximately 6% of the nodules by quantity (this corresponds to 20% of the mass).

The nature of selective collection is the ability to decide between which nodules to collect and which nodules to leave undisturbed. There are several strategies for this, and Impossible Metals has stated the company will seek guidance from scientists and regulators.